Page 1 of 11

A quarter of a century, more or lessFirst things first: I know I do make it hard for some players to appreciate my work. I don't dress bad games in fancy outfits. It's content that matters and as far as boards and pieces go, mindsport has always chosen for non-distractive simplicity.

As far as publicity and presentation go, mindsports has in the past years been one of the few platforms where my work could be found and played. In all other respects I've kept my distance from the world of abstract games for over three decades, watching tactical hypes come and go, while strategy games were still dominated by the classics.

Take Havannah. I knew it to be a good game, somewhere between Hex and Go, from the day of its invention, when as a player I was still at the very bottom of the strategy tree. On other platforms, like Richard's PBeM server, it was well hidden in a multitude of games, it's qualities becoming apparent ever so slowly, because it is a strategy game and requires a substantial effort before it starts paying off.

I didn't push Havannah and I didn't try to market it anew because I knew it would fail for that very reason, as it did in the early eighties. Nor did I try to get any other game on the market, because those I care about would either fail for the same reason, or there would be no need to market them because they employ regular material, like Dameo or Bushka. And for those I don't care about, say quickly understandable tactical games like Hexade of Shakti, it simply seemed too much trouble. I was an inventor, I'm not and have never been a merchant.

It took the game community some thirty years to discover Havannah. The breakthrough came rather unexpectedly when Richard Malaschitz decided to implement it at Little Golem, where a flourishing game community can choose among a number of excellent abstact games. Here a number of good players were able to direct a lot of new players to the game, many of whom were Hex players with ample experience in 'reading' the hex plane. With some world class Hex players taking up the game, and some world class programmers taking up the challenge regarding its programmability, it got the boost it needed to finally be discovered as a true 'mental sport weapon', and one that at the time seemed among the least likely to be cracked by a computer program.

A 'game whisperer'

The hard part to understand is: I knew that from the day of its invention. As a child I already felt Draughts as an 'organism' one had to consult rather than to direct regarding strategy. It was very much 'specific' thinking because I hardly played anything else. Draughts felt very much like judo, which I also practiced in those days: using the opponent's kinetic energy against him.

It was the 'Go in a petri dish' experience, feeling one with a game of which I had only shortly before understood the rules, that showed me that this particular vision was not limited to Draughts. The ability shifted from the specific to the generic. Eventually I turned out to be able to thus 'identify' with some uniform games, provided the rules were effectively taylored to suit the game.

What I am able to 'see' is some games' behaviour at the high end of the strategy tree, up to master level, if applicable (because not many games allow that qualification). It only gradually dawned on me that this 'generic' vision was not a common quality amongst players, or even inventors. Unfortunatlely it is limited to a small class of games that I would label 'organisms' rather than mechanisms.

So there I was, slowly discovering that I was a 'game whisperer' of sorts. Meanwhile the 'strategical' landscape remained unchanged, dominated by the classics, with Chess, Go in the center, Draughts, Shogi and Xiangqi off center, a couple of 'modern classics' like Othello and Hex in the periphery and an unrelenting parade of 15-minutes-of-fame tactical games in an ornamental role, many nice enough, but some desperately bad. You've seen them all come and go and not much has changed over the years. Barring the odd exception, like Trax, no strategy game will reach the market, or live if it does.

It's the economy, stupid

The classics require a certain amount of time and effort to be invested, but they can be trusted to deliver: they've done so for ages. But what about trusting a new game?

For organic games I can usually tell from the rules whether they can be trusted to deliver or not. But most people can't. They have to trust the inventor, the manufacturer and the advertising agency, and barring one or two inventors, they're all in it for the money. A good game is a game that sells. For a game to sell it must be easy to learn and 'fun to play'. By the time you figured out the fun is be short lived, there's a new hype on the shelves where you have to trust the inventor, the manufacturer and the advertising agency. It's the economy, stupid. Manufacturers will not market strategy games, although they like to misuse the qualification whenever and wherever possible. A strategy game requires more than isolated players can bring to the table: clubs, books, teachers, a whole infrastructure. In the absence of it the game will fail, so who can blame them. If you want to make money in the remaining niche market, you're dependent on tactical games and inventors thereof. But to paraphrase David Pritchard: anyone can call himself an 'inventor of abstract games' and unfortunatly some people do. To draw attention to their brainchildren, inventors tend to seriously overrate and overstate the qualities of their games. In consequence it is impossible for an inventor to escape the suspicion of bias.

It eventually led to the sarcastic opening remarks of MindSports:

"We humbly acknowledge that old games are always better because inventing games is one of two human activities excluded from progress. The other one is the brain activity of people adhering to that point of view."

It's an expression of my own frustration, because I'm not in it for the money.

The core

What drove me was the hunt for pure simple new and better strategy games. And I succeeded.

With Grand Chess, which may not be a replacement of Chess, but it is an improvement (as the many rip-offs show).

With Dameo, which I know to be the best 'draughts weapon' around. Far better than International Draughts.

With Emergo, a joint effort with Ed van Zon, and the essential implementation of 'column checkers', coupling a basically simple strategy with an uncanny combinatorial depth.

With Symple, an essential way of inticrately merging 'territory' and 'connection' and the cradle of the move protocol that bears its name.

With Sygo, which uses that very protocol to create a Go variant without cycles and thus free of rules to address them.

These are my best games, and I don't sell them, I offer them. I ask you to trust me on this, lest it should take another thirty years for them to be 'discovered'.

They will require an effort, even more so because good players are as yet scarce. And if you happen to meet one, then the 'lose-fifty-games-first' rule may apply inherently (although no such good players may exist yet). They also will reward the effort invested by showing no end to their strategical and tactical intricacies, and by showing their beauty whenever good players meet.

The pride and sorrow of Draughts

Before turning to the actual stories of Bushka, Dameo and Emergo, I want to say a few words about 10x10 International Draughts, called 'Draughts' here for short, as opposed to its ancestor Anglo-American 'Checkers'. Draughts is big in the Netherlands, Russia, France, Brazil, Suriname and a lot of African countries. There are in fact some 70 national associations. Yet there appears to be a worldwide division between it and the other disciplines. MindSports has a large player-base, partly because it is one of only a few places where the game can be played. It doesn't appear to be taken quite as seriously as Go or Chess. Why? Because Draughts is a great game, but a flawed 'mental sport weapon'.

Historically, at least in the Netherlands, Draughts is a 'proletarian' game, not taken quite that seriously by the 'upper class' Chess community. This is somewhat unjustified. Completely unjustified if you're a Draughts player. You have to fight, for your right, to play Draughts! Flat is beautiful! Say it loud, I'm flat and I'm proud!

In short, Draughts players suffer from an inferiority complex while in loud vocal denial of it. To add insult to injury, they damn well know something is wrong, or there wouldn't have been 25 suggestions (in dutch) to reduce the problematicly large margin of draws in a recent poll under Draughts players. If there is no problem, why go to such lengths to solve it?

Draughts players are sitting in a split: They've fallen for combinations like this one, the one that marks the start of my childhood fascination with the game:

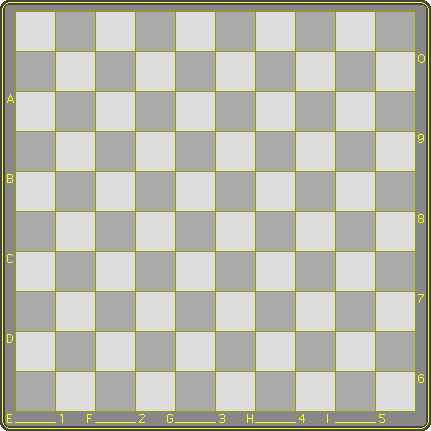

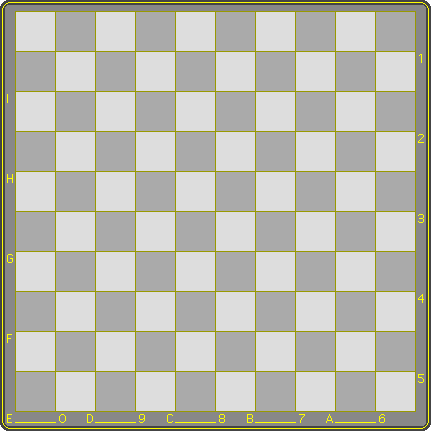

| |||||||

You don't find that in Checkers. In fact, barring Turkish Draughts and its derivates, you don't find anything similar anywhere. And there's more where it came from, see coups and problems.

There's so much beauty in this game that I find it strange that its presence on the web is so modest compared to say Chess or Go. Draughts players tend to consider it another indication of their not being taken quite seriously by the games world at large. It only strengthens their dedication to 'defend' their game.

But the annoying draw devil persists - there's no way around it. And players who are denying the problem while trying to solve it, open the door for even more mockery. Which of course only widens the gap between them and the rest of the games world.

Draughts isn't essential like Checkers. Choices were made during its invention and eventually these converged to a set of rules that perfectly suits the game's spirit: it feels at home in it and rewards us with miracles like the one above, and not in small amounts either. I agree fully with Ton Sijbrands that the game cannot be 'improved'. The problem is inherent. Draughts is a great game that deserves a lot more attention from the games world. At the same time it is a flawed sport weapon where it counts most: at top level match play.

Why this introduction then? Because the game's framework, the set of rules, has proven itself beyond any doubt. The significance of some of these rules may not always be immediately obvious to a novice. Think of a long-range king, compulsory capture, the precedence of majority capture, the rule that a capture must be completed before the captured pieces are removed, the rule that a piece may not be jumped more than once during a capture, while a square may be visited more than once, and the rule that a man visiting the back rank during a capture, but not ending its move there, is not promoted. In the course of learning the game the same novice will discover how it all works together to make possible the 'coups' and the miracles in the problem sections. It is all so well organized that I've taken it as the basis for both Dameo, where it serves a different yet similar way of movement and capture, and Bushka, where it serves an altogether different way of capture. Here we go.